Post-Residency Interview: Tamara Staples – Side Effects May Include

|

| ©Tamara Staples |

Tamara Staples, recipient of the Critical Mass 2014 Rauschenberg Residency award, produced a very notable project – Side Effects May Include – that was on exhibit (March 18 – June 11) at the San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art. Tamara developed this body of work during her residency time on Captiva Island and we are honored to talk to her about it.

Recently, a social media post by a curator asked the public for names of photographers who have used their work to process the death of a loved one, and the query sparked an outpouring of responses – names of photographers who have creatively found solace in their grief through their work. Tamara Staples is included in this group – she began this body of work after the suicide death of her sister, who was over-prescribed psychiatric drugs for her bipolar disorder. Side Effects May Include is Tamara’s visual epitaph to her.

Laura Moya: Tamara, this installation is more like a decorated set than a traditional exhibition. On one hand it looks like a welcoming bedroom, yet one immediately realizes there is a dark undertone. Tell us about the arc of this project – from conception to development to exhibition.

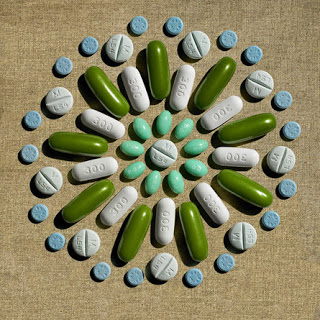

Tamara Staples: Following the death of my sister, I made an image with pills in the shape of a genetic strand. And then I made some black and white images of frailty and loneliness. I was grieving, of course, and I’ve always used creativity as an outpouring. This tragedy haunted me and I needed to make work around it. I asked my sister’s husband to send the contents of her medicine cabinet because I’d seen first hand her relationship to her medication, and they provided a visual. When the pills arrived, dumped into a box, sans bottles and information, I had no idea what I would do with them.

There was a year of picking through them, separating them into same kinds and colors then making patterns and photographing them in shapes that made sense. When using traditional two-dimensional photography, I found the images lacked impact. I began to think about what it is to suffer the ups and downs of a bi-polar disorder. I always admired my sister’s eccentricity, but this charisma could manifest itself in less pleasant ways. She was a hoarder of the highest degree and her house always smelled of 9 rescue animals and was packed from ceiling to floor with trash and junk from the spending sprees at thrift stores. However, when she stepped out of the house, she was put together like a runway model, and she was beautiful. However, I always came back to the medication, thinking about the amount of drugs in her possession and the effects they were having on her mind and body. All of it together suggested a suffocating atmosphere and I wanted to relay something deeply engaging.

It was around this time that I ran into Christopher Rauschenberg and Janet Stein in Chelsea at a photography gallery near my studio. I was working on the “pill project”, taking advantage of the galleries close by for inspiration. Previously, I’d met Christopher and Janet at FotoFest, and from there I’d been invited to show my purebred poultry portraits at Blue Sky Gallery. More recently, I had been chosen for Photolucida’s Top 50 through Critical Mass. Christopher and Janet invited me to a private portfolio showing that week. I felt timid about showing the new work, but I really needed some feedback. Janet is a nurse practitioner and was drawn to the work immediately, introducing me to the idea of polypharmacy. The following week, I was invited to be an artist-in-residence at the Rauschenberg Residency in Captiva, Florida as one of the Photolucida Top 50 awards. Not only was this the most important event in my artistic career, but now there was something new: the obligation to see this work through. It was terrifying.

I’d never considered activism as part of my work, but making art in “Bob” Rauschenberg’s studios infused me with ideas that worked on a subconscious level. The 5 weeks I spent at the residency in Captiva were life changing and helped foment my artistic practice as well as defining me as an artist.

The design of this project slowly evolved to be more sculptural. The experience needed to be immersive. I was thinking about the physicality of the home as a place where people suffer from mental health challenges. Considering the most intimate spaces, the bedroom was top on the list: a place one goes to be consoled, to rejuvenate, to retreat. The objects in the bedroom needed emotional weight: the bedspread envelops, the curtains holds back daily pressures, clothing represents public life, the walls surround and protect. I employed the pill patterns I’d photographed to create the fabrics and paper. And from that: quilts, wallpapers, pillows, framed artworks, dresses, an upholstered chair, and lastly a looped video of undulating water surfaces, to remind the viewer of the tenuous flow of our physiological selves.

|

| All images ©Tamara Staples |

Once the bedroom was designed, I researched the pills from my sister’s medicine cabinet. I worked with the talented book designer, Lynne Yeamans, to create a hardbound book of the inventory. I employed a pharmacist to fact check my work before it went to print. I wanted to lay bare the elements of my sister’s demise. Once the research was exhaustive, I entitled the project Side Effects May Include. I was convinced that however it may have happened, my sister was overmedicated. This didactic portion of the project became the fulcrum of the piece. To complete the circle, I wrote a letter to my sister’s doctor explaining my perspective and asked him point blank: How could this have happened? Who is culpable? I sent him the letter via mail to him, and I included a copy of the book. This letter became the artist’s statement for this project.

LM: A panel discussion took place at the end of May titled The Making of an Epidemic: Polypharmacy in the Treatment of Mental Health. Please give us some background on the definition of “polypharmacy“ and what California’s SB 482 law is. Why is this now considered an epidemic? Who were some of the participating panel members?

TS: Polypharmacy (from Merriam Webster Dictionary): “The practice of administering many different medicines especially concurrently for the treatment of a single disease; also: the concurrent use of multiple medications by a patient to treat usually coexisting conditions and which may result in adverse drug interactions.” My sister had been diagnosed as bi-polar, but had other physical ailments such as a thyroid condition, severe nasal congestion, herpes, and was anorexic. As the pills regiment became more complicated she added aids for her digestion and stomach problems, along with pain medications and weight loss pills. While under her doctors’ care, there was no attempt for nutritional or talk therapy. At last count, there were 114 prescription and over-the-counter medications. I have no idea how many of those she was taking at once, but I imagine there were too many.

I learned of California’s Senate Bill 482 through Cathy Kimball, the Executive Director of ICA San Jose. The bill was shortly up for amendment. It was asking for the health care providers to review a patient’s controlled substance history before prescribing any patient medication for the first time and then reviewing every 4 months.

I met Cathy in Houston at FotoFest in 2016 and it was there that I presented to her a photograph of a diorama I’d made of the proposed bedroom, the book, and a quilt sample. Cathy instinctively understood the work and our talk turned to a position of activism immediately.

Cathy invited me to have a show at ICA. The first conversation involved putting together a panel discussion around the topic of polypharmacy, because so many questions remain after viewing Side Effects May Include. After all, this is about one person’s experience who paid the ultimate price. I began to research organizations that highlighted the phenomenon of polypharmacy. Robert Whitaker founded the non-profit organization Mad in American and wrote the very shocking Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America. In the book he examines the introduction of medications in the 1950’s. His research shows that with illnesses such as heart disease and diabetes, the drugs drastically reduced deaths, where in the case of mental disabilities, the drugs increased not only deaths, but the actual symptoms, forcing many to become disabled for life, which was not the case pre-psychotropics. One in five people in our country are taking some form of psychiatric medications.

Robert pointed me to Yana Jacobs from The Foundation of Excellence in Mental Health. She lives and works in the Bay Area, where Side Effects May Include was to take place. Yana was fundamental in gathering the panelists and saw the value in connecting the foundation to the message of the work. She is such an impassioned advocate of treating the mentally challenged without medication and I was eager to learn from her and all the panelists. Yana brought David Lo MD, Counselor and Psychological Services from San Jose State University, where he offers balanced and thoughtful treatments to students on campus; Kathy Forward, representing National Alliance on Mental Illness; and Dina Tyler, who has “lived experience” and is now drug free. Dina works with an early psychosis intervention program and is co-founder of Bay Area Hearing Voices. Yana, Chief Development Officer, was a panelist along with myself. Cathy Kimball officiated and was able to thread together a meaningful conversation with her insightful questions. The audience equaled about 30 – every person there to educate themselves, whether they worked in the psychiatric or medical field or they had been touched in some way by mental challenges.

The panelist discussion was powerful. What moved me most was the personal story of Dina Tyler, who had gone through the system and decided to live her life drug free. This was hard fought, and against the advise of everyone, but mostly her caregivers. She had grown up hearing voices and she posed such simple but poignant questions like: “What is normal?” and “Is there room for spirituality within what people perceive to be the marginalized?” Being saddled with a mental “disability” is a very personal assault. Often times people diagnosed as such lose their rights as human beings on a basic level.

It turns out that there are many people who suffer the same fate. For example, recently the musician Chris Cornell took his life after many years of taking medications for his mental challenges and it made headlines.

LM: There is something about the fact that you handcrafted many of the elements of the installation (a dress, a quilt, wallpaper) that makes it read as a very intimate experience, combined with the fact this is a bedroom, a very intimate place. This project connects extremely personal feelings with larger issues of mental illness, addiction, the medical field, and pharmaceutical industry. How does one creatively travel such a long distance?

TS: The project needed to feel personal, because it is. I’ve always been drawn to fabric arts and have spent some serious time working with fabric. Although I love the process, I was not prepared to take on so many different disciplines, so I hired competent artisans to make the objects for this project. I really enjoy collaborating with others but this was such a challenge in that I worked with 10 talented people to put this room together. But what joy it was! The list included a seamstress, a quilter, a printer for the framed artwork, an image specialist who helped create the designs, the company that printed the fabrics, several designers, an upholsterer, a video editor, and a wallpaper company. And the project could not have been a success without the ICA exhibitions manager Mike Oechsli and my partner Jason Stilp who realized the final room.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention my sister’s husband, who lost his wife. He supported my efforts in this project with such generosity. His participation was crucial to the final piece. Together, we celebrate her life, and always will.

I loved that last question: How does one creatively travel such long distances? So often as artists, we are constantly searching for inspiration, to be moved with a desire to make something poetic. And sometimes, in this case, a personal tragedy stands before you and you grieve in the only way you know how: through creative process. I guess the answer is, I had to.

Art is restoration: the idea is to repair the damages that are inflicted in life, to make something that is fragmented – which is what fear and anxiety do to a person – into something whole. – Louise Bourgeois

LM: Now that Side Effects May Include has been out in the world, and has gathered energy and produced important conversations around it, is there a next step forward?

TS: I sure hope so! I am currently working with Cathy Kimball toward that end. I would like to see this show in other cities with other panel discussions. It is so clear to me that this issue is begging to be opened up to the general public and once we start talking and connecting the dots, real change could occur. I’d like to hear the pharmaceutical companies defend themselves.

|

| ©Tamara Staples |

Artists have no choice but to express their lives. They have only, and that not always, a choice of process. This process does not change the essential content of their work in art, which can only be their life. – Anne Truitt, Daybook, The Journal of an Artist