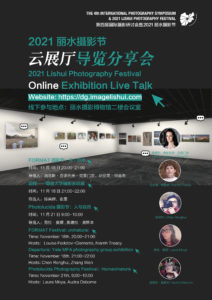

Human/Nature Live Talk at the Lishui Photo Festival

Curator: Laura Moya, Executive Director, Photolucida Associate Curator: Isabella Wang, Lishui Photography Festival

Exibiting Artists: Deb Achak, Debe Arlook, Thomas Georg Blank + Işık Kaya, Aaron Blum, Peter Bogaczewicz, Goseong Choi, David Ellingsen, Peter Essick, David Freese, Adriene Hughes, Serge J-F. Levy, Holly Lynton, Amanda Marchand, Diana Cheren Nygen, Stefan Petranek, Meg Roussos, Jennifer Shaw, Miranda Schmitz, Sara Silks, Noriko Takasugi, Amanda Tinker, Alex Turner and Barry Underwood.

CURATORIAL STATEMENT:

“If as individuals we can improve the geography only slightly, if at all, perhaps the more appropriately scaled subject for reshaping is ourselves.” ― Robert Adams

A turning point in the history of photography was the 1975 exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, curated by William Jenkins at the George Eastman House, which signaled a shift away from traditional depictions of landscape. The show featured 10 photographers (including Robert Adams) who examined the American landscape in a new way. Instead of producing images of grandiose scenery such as those sourced at national parks, the artists produced imagery exploring the byproducts of postwar suburban expansion: tract home developments, industrial parks, newly constructed freeways.

What was remarkable about New Topographics was not only the newness of the photographic content, but how the work made viewers feel. By placing importance on human presence (instead of erasing it), the photographs guided people into a place of responsibility toward the future of the landscape and gave them more of a connective bond to their physical environment.

Decades later, photographic artists continue to produce work that examines the different ways that humans connect with, construct, or clash with elements of the natural world. But now it is a more sophisticated telling – an examination of deeper philosophical ideas, a conversation about more than geographic terrain. The relationship between humans and nature is complex – it is both wonderfully symbiotic and fraught with uneasiness.

The clash of human development and pristine nature is visually illustrated by several artists in HUMAN/NATURE – Peter Bogaczewicz’s ‘Surface Tensions’, Peter Essick’s ‘Construction Sites’ and David Freese’s ‘Iceland Wintertide’ show the subtle and not-so-subtle meetings between human development and the natural world. Alex Turner’s ‘Blind River’ gives us ghostly glimpses of humans and animals moving through the Sonoran Desert by way of unmanned camera systems and software recording patterns of movement. Thomas Georg Blank + Isik Kaya show us in ‘Second Nature’ how cellular towers disguised as trees in the Southern California landscape illustrate the clash between utility and nature. On the other end of the process spectrum, Aaron Blum constructs a poetic ode in platinum (‘The Sweet Promised Land’) to his place of origin – the Appalachians – admitting that visual elements are both real and imagined, the results of his intricate process becoming a legacy for his children.

David Ellingsen (‘Falling Boundaries’) and Diana Cheren Nygen (‘The Persistence of Family’) both explore the concept of time-travel by using personal archival negatives. This interweaving of past and present realities illustrates the blending of family histories and the environmental crisis involving old growth forests in British Columbia (Ellingsen) and using the New England landscape as the geographic point to contemplate familial identity (Nygen). Deb Achak (‘Sun in My Mouth’) uses visual metaphor (people and landscapes) to convince us that everything is connected through universal energy fields, we just need to pay more attention.

Several artists show us how emotional states can be metaphorically played out in the landscape: Debe Arlook (‘Foreseeable Cache’) uses Southwestern landscapes to illustrate her practice of meditation to negotiate the stress of these turbulent times. Serge J-F. Levy (‘2900 Miles and Other Jumping Cholla’) visually records daily omens in his desert environment that he considers premonitions of his father’s eventual demise. Goseong Choi (‘Counting Shadows Blackens My Fingertips’) finds solace in his immersion in the natural world while searching for clarity on loss and the fragility of life. The work of Miranda Schmitz (‘Black Waves’) is an expressionistic project that explores the darkness of suicide and grief through depictions of just-as-dark landscapes.

Natural disasters are understandably topics that artists explore; hopefully the creative process helps to ease anxieties: Jennifer Shaw (‘Flood State’) uses photograms to illustrate her fear of increased rainfall, rising tides and flooding in her home state of Louisiana. Sara Silks (‘Prairiefire’) reinvents images from Kansas prairie prescribed burns to help her work with her feelings about the world being on the edge of environmental collapse. Noriko Takasugi (‘Musuhi’) produces an illustrative narrative about the aftermath of the Fukashima disasters by showing how people can rebuild community – by re-connecting to the land, honoring the role of traditional gods, and continuing to perform ancient equestrian cultural traditions. Stefan Petranek’s work (‘The Future is Broken’) seeks to create a dialog with the viewer about alarming climate science data by placing it over personally significant landscapes and striving to spark our perceptions of rapidly evolving nature. Barry Underwood’s luminescent tableaus (‘Scenes’) are filled with light, color and geometry and are meant to prompt viewers to think about how humans have consistently manipulated the landscape to fit our needs.

HUMAN/NATURE also shows work of a more peaceful co-existence with the natural world: Amanda Marchand’s abstract collage series ‘The World is Astonishing with You in it: A 21st Century Field Guide to the Birds, Ferns and Wildflowers’ uses the temporality of the lumen process, along with found family field guides, to bring reference to endangered plant and animal species. Along similar lines, Amanda Tinker (‘Small Animal’) uses a view camera to make elegant constructions of estranged experiences of the natural world – birds, butterflies, and twigs – that become mere objects of contemplation disconnected from nature itself. Adriene Hughes (‘The Secret Life of Trees’) uses infrared film and embroidery to emphasize lines of silent communication between trees – via biochemical and electrical signals – perhaps warning each other about an impending forest fire. Meg Roussos’ series ‘Pseudo Night’ gives us eerie single-track landscapes that hover between day and night, the carving of empty roads showing the impact of human presence through absence. Holly Lynton’s body of work ‘Bare Handed’ is dedicated to showing a resilient community that continues to choose manual methods of working and connecting to their rural environments, despite technological advancements and the development of agri-business.

These photographic artists have captured and constructed landscapes to evoke heavy emotional metaphor, highlighted the tension between encroaching development and untouched landscape, and warned us of dire environmental effects caused by our relentless impact on the natural world. But there is optimism, too: perhaps trees can really talk to each other, desert landscapes can offer redemption, coyotes still run wild at night. Mankind and bees will continue to closely co-exist, and ancient cultural traditions honoring horses are still carried out over centuries despite natural disasters. All these photographic stories explore the complex relationship between humans and nature and no singular conclusion is clear – other than acknowledging we have the option to reshape our place in the world; we must decide for ourselves how we move through it.

All artists in the HUMAN/NATURE exhibit are from Photolucida’s Critical Mass 2020/2021 programming.